Anguilla is Known for Its Caves?

Though Anguilla is only 16 miles long and three miles wide, a lot of interesting attractions and natural landmarks are packed into this tiny island from above to below. The 213 foot high Crocus Hill towers over the otherwise flat limestone landscape, and a giant underground cave called The Fountain pumps fresh water into Shoal Bay. Other caves include Cavannagh Cave where you will find the remains of extinct giant rodents and Iguana Cave where you will hear the sounds of thousands of fluttering bat wings.

For more information, visit https://www.facebook.com/axanationaltrust

The Fountain Cavern

“A 16 foot tall stalagmite carved in the shape of the Taino supreme being, Jocahu, is merely the largest of the many ancient rock carvings found within the Fountain Cavern. This underground cave 50 feet beneath Anguilla’s surface was once a major pilgrimage and worship site. Ancient petroglyphs dating from roughly the year 900 surround the two freshwater pools inside the cave structure close to Shoal Bay ~

Located on the island of Anguilla (18°15’02.91″ N 63°02’07.05″ W), Fountain Cavern is an exceptionally well-preserved Pre-Columbian archaeological site located 250 m inland from lower Shoal Bay East on the northeast coast of Anguilla. The site lies within the boundary of Fountain Cavern National Park at a depth of 20 m below ground surface within a two chambered limestone cave approximately 50 x 30 m in size.

Fountain Cavern features a unique assemblage of Amerindian rock art and archaeological deposits associated with a subterranean freshwater pool. The rock art features, including a large stalagmite statue, are illuminated by natural light from the six m² entry hole in the cave’s ceiling. Pitch apple (Clausia) and Fig (Ficus) tree roots like those growing down from the entrance today likely provided the means of access in Pre-Columbian times (a steel ship’s mast ladder was installed in 1953).

Archaeological excavations indicate that Amerindians first utilized the site for ritual purposes around A.D. 400 and continued using the cave until at least AD 1200. Based on this evidence Fountain Cavern is the oldest known and longest used ceremonial cave site in the entire Caribbean. As such, Fountain Cavern represents an extraordinary example of Amerindian cultural heritage.

Fountain Cavern was first recognized as a highly significant Pre-Columbian archaeological site in 1979. The Government of Anguilla designated the site and surrounding area as a National Park in 1985.

In 1986, the Carnegie Museum of Natural History conducted the first systematic archaeological investigation and the National Speleological Foundation studied the viability of developing it as a “show cave.” That year, the Anguillan government and the Anguilla Archaeological and Historical Society also constructed a grate over the cave opening to protect the resource and permit resident bats to come and go freely. In 1996, the Anguillan government established the Fountain National Park Corporation and made the Anguilla National Trust the sole shareholder with responsibility for development of the site.

In 2006, an international panel of experts assembled by UNESCO World Heritage ranked the site as one of the 10 most important rock art sites in the Circum-Caribbean region. In 2007, as part long-term planning, the University of Vermont initiated laser mapping of the cave with support from Anguillan government, Anguilla Archaeological and Historical Society and Anguilla National Trust.

Fountain Cavern demonstrates the artistic capabilities and spirituality of the Amerindian people who resided in Anguilla and broader Caribbean prior to the arrival of Europeans and Africans. As such, the site is a monument to the peoples and cultures destroyed within a century of European Contact. There are no other archaeological sites like Fountain Cavern known in the eastern Caribbean/Lesser Antilles and less than a handful of comparable sites are recorded in the islands of the western Caribbean/Greater Antilles. In fact, at one of the only other comparable sites in Cuba, a carved statue head like the one preserved in Fountain Cavern was cut off and carried away to a foreign museum in the 1920s.

Presently, there are no sites in the region on the World Heritage List that pay tribute to indigenous cultural heritage and very few worldwide that recognize the contributions of smaller societies to human prehistory. The nomination of Fountain Cavern would therefore help address both an underrepresented world region on the list and an under-represented scale of society. In addition, nominating Fountain Cavern would have a major educational benefit in the eastern Caribbean by acknowledging the international value of the region’s cultural heritage.

Fountain Cavern bears exceptional testimony to a cultural tradition that has disappeared as a unique window into the spiritual tradition of indigenous Caribbean peoples. Spanish chronicles document that the culturally related Taíno people of the Greater Antilles believed that the sun, the moon and the first people all emerged from caves. They built shrines in ceremonial caves to induce rainfall and buried elite individuals within them. Fountain Cavern’s stalagmite statue places the site within the Taíno mythological realm. A masterwork within its cultural context, the head of the statue is carved into a likeness of “Yucahú,” the “God of Yuca” (cassava), a spirit of fertility.

Amerindians used the natural space and geologic formations of Fountain Cavern to reveal and engage with the supernatural world. The three-dimensional statue overlooking the freshwater pool, associated artefact deposits and the gallery of at least 12 other petroglyphs establish that Fountain Cavern was a highly significant place of worship. Fountain Cavern has outstanding universal value as a monument to Amerindian religion and spirituality and as the earliest known site of its kind in the Caribbean. As such, Fountain Cavern represents the cultural equivalent of a listed site such as the Catedral Primada de America, the oldest cathedral in the New World.

Within its cultural context the stalagmite statue in Fountain Cavern is a masterpiece of creative genius. Amerindian sculptors transformed a speleothem in the center of the cave into the personification of the deity Yucahú, a spirit of fertility. Carving a face into the head of the stalagmite, Amerindians memorialized a supernatural revelation in a three-dimensional statue. The imposing manifestation of Yucahu overlooks the pool in the chamber, presiding over a (rare) life-giving source of freshwater within the sacred subterranean context of a cave. For Amerindians, participating in rituals or collecting water, the statue was undoubtedly awe-inspiring. Fountain Cavern was utilized as a ceremonial site for more than 1,000 years and as such, the monumental art in the form of the stalagmite statue of the fertility god Yucahú represents the interchange of cultural values relating to the peoples’ origin mythology and spirituality.

As a portal into the underworld, the cave served as a ceremonial center for Amerindians in the region, a place where cultural values were shared and reaffirmed. The Fountain Cavern bears exceptional testimony to the cultural traditions of indigenous Amerindian populations that disappeared soon after European contact.”

From: Mr. Merwyn F. Rogers and Mr. Karim V D Hodge Status Permanent Secretary, Environment & Director, Environment Address Ministry and Department of Environment Ministry for Home Affairs and Environment Building The Secretariat , P.O.Box 60, The Valley, AI 2640 Anguilla, B.W.I.

Cavannaugh Cave

Excerpt From: http://www.wondermondo.com/Countries/NA/LesserAntilles/Anguilla/CavannaghCave.htm

“Located on the island of Anguilla (18.2115 N 63.0717 W), near the north-western coast between The Valley and North Hill, in the southern side of Katouche Valley, north from the Governor’s residence, Cavannaugh Cave is a small, rather unsightly cave in the limestone cliffs. This is the most likely place where in 1868 were discovered large bones – remains of an extinct rodent Amblyrhiza inundata, which was up to 200 kg heavy.”

In Pleistocene, when the sea level was considerably lower than now, Anguilla together with the nearby St. Martin and some other islands formed a single landmass.

It seems that hutias – nutria-like rodents of Caribbean – had suitable life conditions on this island and were not endangered by predators. As a result these animals became larger and larger with every generation until they were up to 2 m long and up to 200 kg heavy. Existing hutias today are some 2 kg heavy and 0.2 – 0.5 m long, while the world’s largest living rodents – capybaras – are some 50 kg heavy.

Giant hutias of Anguilla – blunt-toothed giant hutias (Amblyrhiza inundata) – were some of the largest rodents ever, but not the largest ones. Some 4 million years ago in South America lived Josephoartigasia monesi – this rodent was up to 1.3 tons heavy.

As the sea level rose in the end of Pleistocene, giant hutias had less and less land to sustain them. Ancient land divided into smaller islands which were too small to maintain large populations of these large animals. As the number of giant hutias fell below 1000 and less, population was not viable anymore and species went extinct.

It is little likely that there were any live giant hutias when first people came to Anguilla circa 1300 BC.

Anguilla has rather many small caves which have formed in the early Miocene limestone. Bats and other animals have lived in these caves for millennia and their dung and carcasses of dead animals accumulated on the cave floor, forming thick layer of phosphatic sediments.

These phosphates – valuable fertilizer – were mined in Caribbean caves in the 19th century. No one knows how many paleontological (and possibly – archaeological) values have been lost in process.

One such sample of phosphate sediments was sent from Anguilla to Philadelphia (United States) in 1868 to estimate the value of fertilizer. Fractions of bones were discovered in this sample and were given to American paleontologist Edward Drinker Cope. The find was very interesting – bones belonged to an unknown, enormous rodent.

Cope asked a physician from St. Martin, H. E. van Rijgersma to look for additional specimens in Anguilla. Rijgersma visited Anguilla several times and brought back fine samples of bones. Unfortunately he did not identify where he found them, he just wrote that bones were found in Bat Cave. Such place name today is not applied to any cave on the island.

It is though known that bones of this extinct animal were found in Katouche Valley and Cavannagh Cave is the most likely place of the discovery.

Katouche or Iguana Cave

Excerpt From: Diana Lambdin Meyer- http://www.buckettripper.com/spelunking-on-the-caribbean-island-of-anguilla/

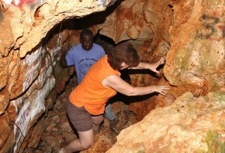

“I’m glad Oliver was leading the way to Katouche Cave, otherwise I could have simply fallen in and never known what had happened.

Just a few hundred feet from the roadway and surrounded by a growth of white cedar and fig trees, Katouche Cave is for the more adventurous caver. Hanging on to the roots of a fig tree, I lowered myself about ten feet down to one rocky ledge and then another. Two or three steps further and it was pitch dark. The cave floor was uneven and strewn with rocks large enough to trip over. It was quite cool in here, like all caves are, and if you were quiet, you could hear the bats fluttering in the darkness a half mile or so away.

Katouche Cave meanders around about three-quarters of a mile. Nothing is so tight or tedious that you have to be on your belly scooting around. Most of the time you are stooped over, taking care not to hit your head on the outcroppings and stalactites. The walls here are not smooth limestone, like Cavannah, so this cave was never under water. The cave has five rooms large enough to stand up in.

Or so says Oliver.

I admit that I got a little claustrophobic and didn’t go as far and deep into the cave as did others in our party.

They loved it and made me feel a little ashamed for chickening out. But at the same time, I did something different than most visitors to the Caribbean do. On the next island I visit, I’ll look for caves to explore and that time, well, I might go all the way.”